Some time ago, while building an API, I though that stacking if statements

depending on function parameters leads to complex business logic. One of the

solutions I found was “methods overloading”, used mainly in Java (and C#).

Shortly put, overloaded method stands out from others because it seems like it has been defined multiple times, each one having different signature. Take a look at this super simple implementation in Java:

class Car {

public static String drive(int speed) {

return "Car is driving with " + speed + " km/h.";

}

public static int[] drive(int init, int target) {

return IntStream.rangeClosed(init, target).toArray();

}

}

There are two methods then are named drive. One accepts one parameter, the

other – two. Calling those methods is straightforward – depending on the

arguments number, the matching one is executed.

I tried to achieve similar results in TypeScript. In short – I failed.

My main problem is the nature of TypeScript itself. Being a JavaScript superset, it cannot alter the language functionalities drastically, just enhance them. Declaring two class methods of the same name isn’t an error per se, but it results in the last one being actually evaluated.

There’s only one thing we actually can do. Overload method declaration:

class Car {

public static drive(speed: number): string;

public static drive(speed: number, target: number): number[];

public static drive(speed: number, target?: number): string | number[] {

if (target) {

const arr: number[] = [];

for (let i = speed; i <= target; i++) {

arr.push(i);

}

return arr;

}

return `Car is driving with ${speed} km/h.`;

}

}

While this certainly works, and even looks nice, it doesn’t give us much. Sure, somebody else will look and know in an instant that this given method has two possible calls. But, without the overloads, is it so different? Removing those two lines still leaves the information that method requires one argument (number), has optional second (number) and returns either string or an array of numbers. The only real gain is the output distinction. But a single glimpse at the method’s body gives it away just as good. And if not, think about simplifying your code.

In my opinion, while this technique is powerful while used in Java, in TypeScript it just fails. Overloading greatest strength lies within the possibility to reduce conditional logic in favor of separated declarations. In TypeScript all we can do is write a different

—

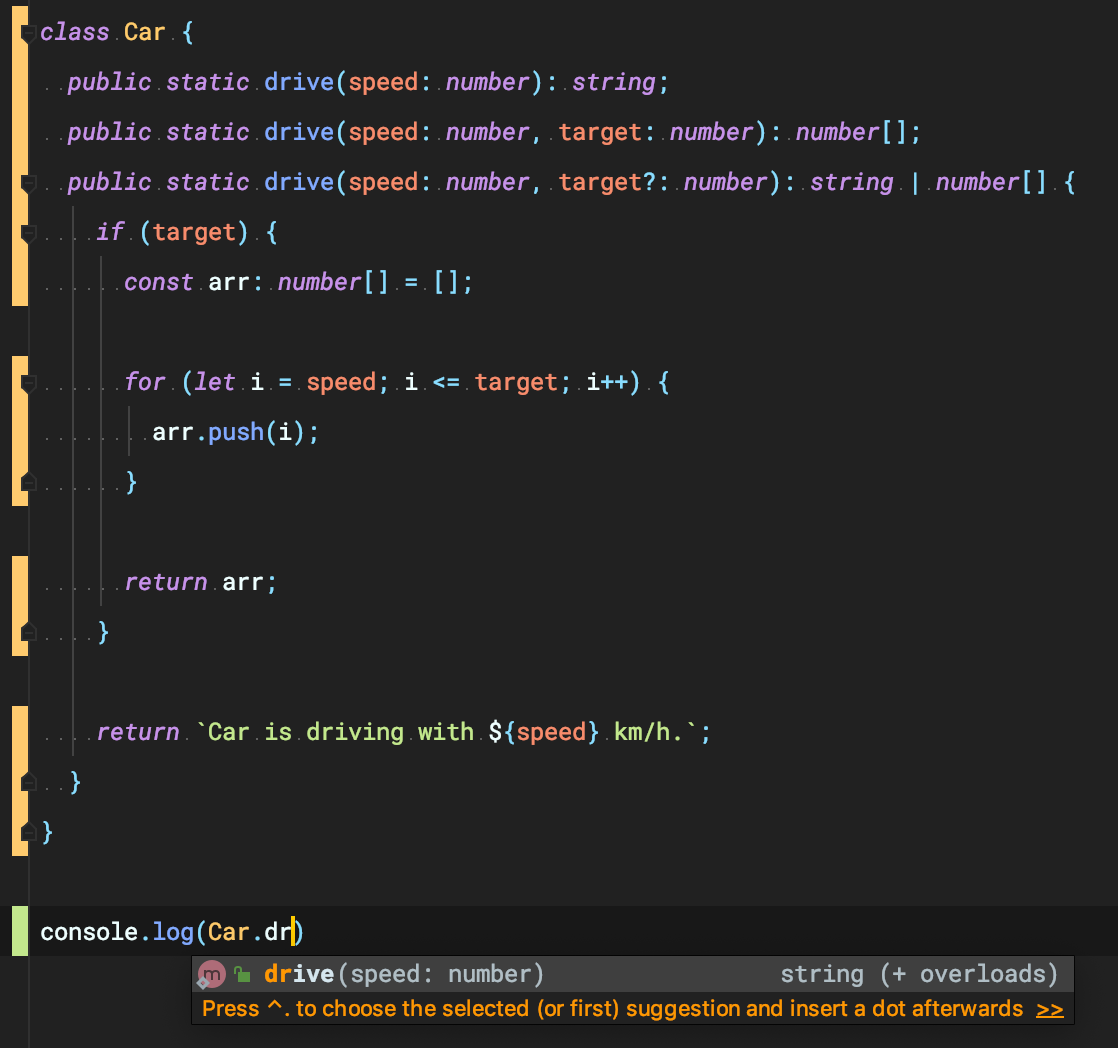

One thing I was hoping for is IDE support. Unfortunately, my one and only IntelliJ doesn’t really care:

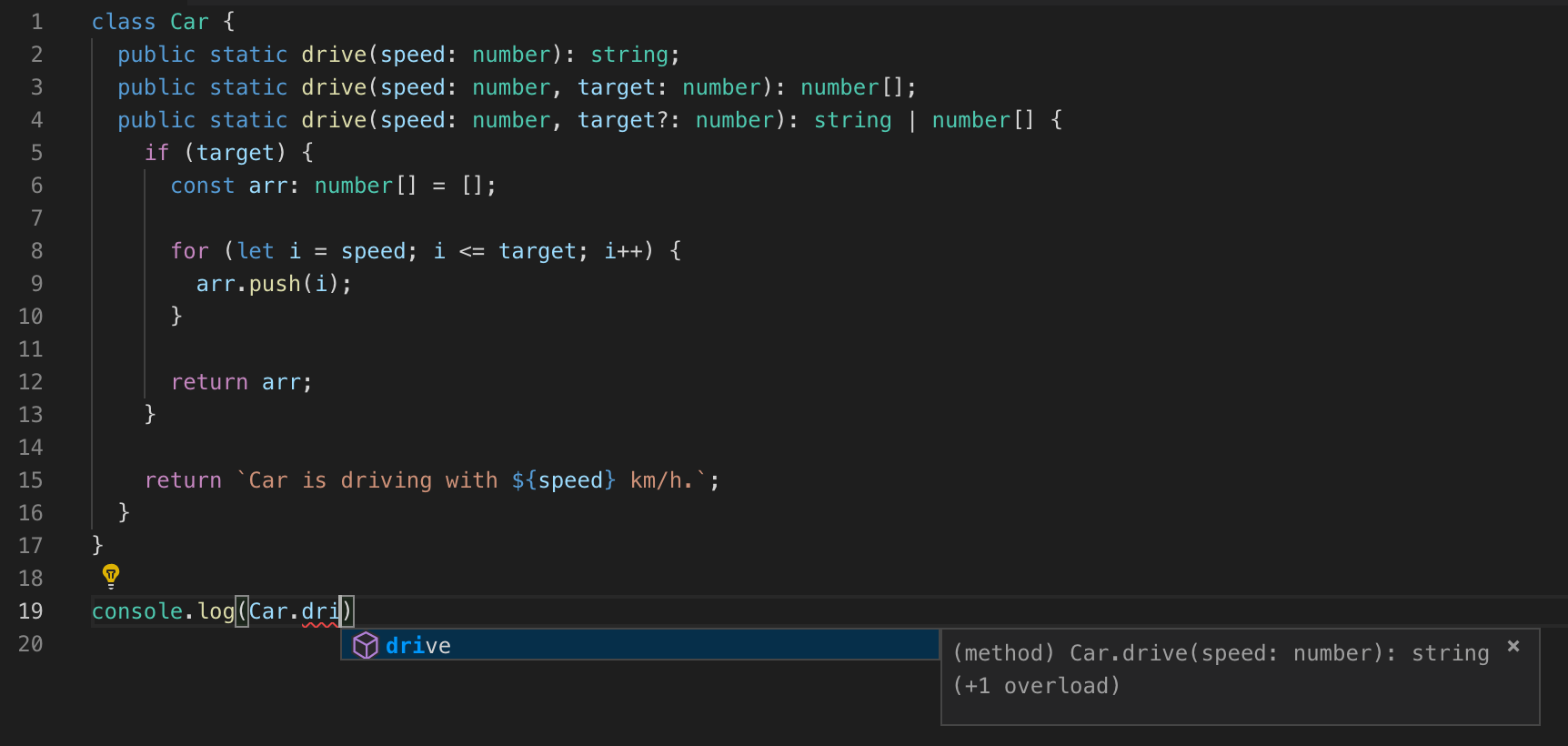

Neither does VS Code:

—